Three physicians’ contributions to the 17th-century masterpiece Hortus Malabaricus remain shrouded in controversy after 350 years

“My 15 years of research to connect the missing links in the history of Hortus Malabaricus hasn’t yielded fruit yet,” said Konkani poet and researcher N Balakrishna Mallya. “But I am hopeful of tracing the descendants of the three great Konkani physicians who played a crucial role in compiling the historical treatise on Kerala’s traditional medicinal plants,” he said.

First published in Amsterdam in 1676, Hortus Malabaricus documents the medicinal properties of flora found in Kerala, Karnataka, and Goa. It was a monumental effort involving contributions from botanists, physicians, and practitioners of folk medicine. Among them were Konkani-speaking Brahmins, whose contributions were formally acknowledged in the Konkani certificate attached to the Herbal Encyclopedia. This document is regarded as the first-ever published record in the Konkani language written in Devanagari script.

“The certificate in chaste Konkani in Devanagari script is very significant as it lent the Konkani language an official validation that in turn gave a moral boost to the language activists at a time when the very substance of Konkani was being questioned,” said Konkani author and Jnanpith winner Damodar Mauzo at an event in Kochi commemorating the historic certificate featured in the botanical encyclopaedia.

Although the original Latin version of Hortus Malabaricus was preserved in select libraries, it remained largely unknown to the public until the late Dr KS Manilal’s translations made it accessible. Manilal dedicated nearly 50 years to translating the work, with the University of Kerala publishing the English version in 2003 and the Malayalam version in 2008.

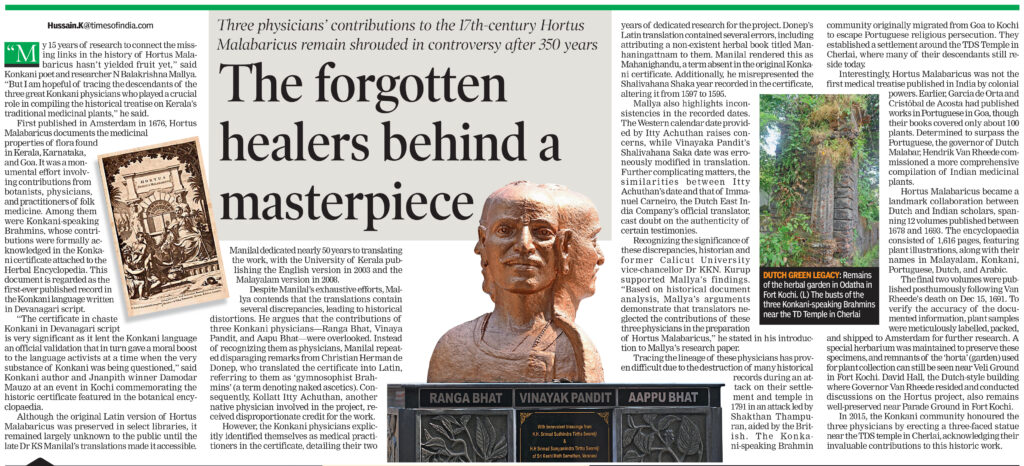

Despite Manilal’s exhaustive efforts, Mallya contends that the translations contain several discrepancies, leading to historical distortions. He argues that the contributions of three Konkani physicians—Ranga Bhat, Vinaya Pandit, and Aapu Bhat—were overlooked. Instead of recognizing them as physicians, Manilal repeated disparaging remarks from Christian Herman de Donep, who translated the certificate into Latin, referring to them as ‘gymnosophist Brahmins’ (a term denoting naked ascetics). Consequently, Kollatt Itty Achuthan, another native physician involved in the project, received disproportionate credit for the work.

However, the Konkani physicians explicitly identified themselves as medical practitioners in the certificate, detailing their two years of dedicated research for the project. Donep’s Latin translation contained several errors, including attributing a non-existent herbal book titled Manhaningattnam to them. Manilal rendered this as Mahanighandu, a term absent in the original Konkani certificate. Additionally, he misrepresented the Shalivahana Shaka year recorded in the certificate, altering it from 1597 to 1595.

Mallya also highlights inconsistencies in the recorded dates. The Western calendar date provided by Itty Achuthan raises concerns, while Vinayaka Pandit’s Shalivahana Saka date was erroneously modified in translation. Further complicating matters, the similarities between Itty Achuthan’s date and that of Immanuel Carneiro, the Dutch East India Company’s official translator, cast doubt on the authenticity of certain testimonies.

Recognizing the significance of these discrepancies, historian and former Calicut University vice-chancellor Dr KKN Kurup supported Mallya’s findings. “Based on historical document analysis, Mallya’s arguments demonstrate that translators neglected the contributions of these three physicians in the preparation of Hortus Malabaricus,” he stated in his introduction to Mallya’s research paper.

Tracing the lineage of these physicians has proven difficult due to the destruction of many historical records during an attack on their settlement and temple in 1791 in an attack led by Shakthan Thampuran, aided by the British.

The Konkani-speaking Brahmin community originally migrated from Goa to Kochi to escape Portuguese religious persecution. They established a settlement around the TD Temple in Cherlai, where many of their descendants still reside today.

Interestingly, Hortus Malabaricus was not the first medical treatise published in India by colonial powers. Earlier, Garcia de Orta and Cristóbal de Acosta had published works in Portuguese in Goa, though their books covered only about 100 plants. Determined to surpass the Portuguese, the governor of Dutch Malabar, Hendrik Van Rheede commissioned a more comprehensive compilation of Indian medicinal plants.

Hortus Malabaricus became a landmark collaboration between Dutch and Indian scholars, spanning 12 volumes published between 1678 and 1693. The encyclopaedia consisted of 1,616 pages, featuring plant illustrations, along with their names in Malayalam, Konkani, Portuguese, Dutch, and Arabic.

The final two volumes were published posthumously following Van Rheede’s death on Dec 15, 1691. To verify the accuracy of the documented information, plant samples were meticulously labelled, packed, and shipped to Amsterdam for further research. A special herbarium was maintained to preserve these specimens, and remnants of the ‘horta’ (garden) used for plant collection can still be seen near Veli Ground in Fort Kochi. David Hall, the Dutch-style building where Governor Van Rheede resided and conducted discussions on the Hortus project, also remains well-preserved near Parade Ground in Fort Kochi.

In 2015, the Konkani community honoured the three physicians by erecting a three-faced statue near the TD temple in Cherlai, acknowledging their invaluable contributions to this historic work.